The word "research" sometimes scares students, because it seems very difficult. It does not have to be! If they think carefully about your goals and methods, anyone can do research. (Note: This is a general guide for many majors, but it was originally written for history students, so many of the examples come from historical research.)

|

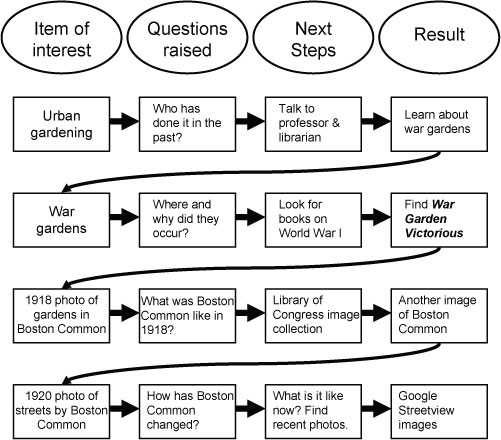

| Early research often means running through many questions. (image from Learning Historical Research, "Asking Good Questions") |

The first thing you need to do is find your research question. It needs to be something that you can prove one way or another. (The existence of God, for instance, is very hard to prove or disprove--I would not recommend it as a research question.) You may need to revise your question as new information comes to you. Don't be afraid of that. Sometimes you need to get some basic information and data on the subject before you can form a theory. Also, make sure your theory is testable (it can be proven or disproven by the research): if there's no way for your research to disprove the theory, what's the point of the research?

Once you have a good question and a first draft of a theory, you can get to the real research.

Styles of Research

There are two main kinds of research, Quantitative (from quantity, meaning 'number') and Qualitative (from quality, meaning a describable but not countable thing, like color or feeling). Good research often uses both styles.

Quantity("Quant")-based research is all about counting and measuring things. It could be the answers to a survey, or the number of miles of paved road at different times, or the number of times in a book that the author says good things about his king. You can be very clever in figuring out ways to measure things that may be hard to find. During WW2, British researchers would listen to German radio and pay attention to seemingly-unimportant things like the price of milk in Paris. If the price was high, that meant that Allied bombing had successfully damaged the infrastructure there, making transport more difficult (and expensive) and therefore causing the prices to rise. There are two main issues when doing research of this kind:

- What do you count and why? You should only measure things that actually give you useful information, and you should be clear about what information a measurement can give you. Logic and creativity are very important when planning your research strategy.

- How do you analyze all the numbers you have collected? This may require some skill in statistics and probability, (for example, if you are dealing with many survey results or historical census data), and may require a consultation with someone from the sociology or mathematics departments if you don't feel confident.

Since answering question 1 is difficult, sometimes researchers start by doing a few interviews or using other qualitative methods to generate theories and ideas before going out and counting a bunch of things. That way, they can be sure that they're measuring the right thing in the right way.

Quality-based research does not use mathematics. Instead, it is based on analysis and interpretation of human society and culture. It can involve interviews, observation of daily life, or close reading of primary sources. You might think that it is easier, since it does not require mathematics, but it can be just as difficult. If you want to do good qualitative research, you need to know about the society and culture of your source (otherwise, you might not understand their answers or ways of thinking). You also need strong critical thinking skills so that you can think carefully about your source.

- Evaluate the source: Who is the source? What is the context? Why are they saying/writing this? How do they know what they claim to know? (Sometimes villagers will tell NGO workers that they are so hopeless and pitiful (even if they are not), because they want the NGO to give them money or other help. )

- Check for bias: Is there anything in the source's background or reason for writing that could affect their answers and make them unreliable? If the source is biased, be specific about what the bias is and what it affects. (A king's official writer will probably not say bad things about the king, for instance. So we should be critical when looking at his statements about the king. But we can probably trust what he says about unrelated things, like if he mentions a flood in a particular province in a particular year.) The classic example for Cambodian students is how Zhou Daguan's Chinese background and audience affect his report of Cambodia c.1295.

- What can you learn from the source? Maybe it gives evidence for how people felt or thought about a certain subject at a certain time, or maybe it gives important information about culture and behavior

|

| No matter your research style, there is always a little bit of the other. (image via vovici) |

Other Points: Coding and Triangulation

If you are working with only a few primary sources or informants, you can just keep detailed notes of your thoughts and analysis. But if you are doing a study of many different sources or people, you might need some form of organization. One way to do this is called coding, which is a way to turn qualitative analysis into usable numbers. Basically, you think of different categories for your sources and then you group them into different categories. For each interview or primary source, you tag it with terms to describe the source and its content (things like "female author," "pro-king," "blames flood on unusually heavy rains" "blames flood on bad government" or "unreliable on dates"). That's a good way to compare many sources, and see if there are patterns. Probably, many of the sources identified as "pro-king" tend to blame the flood on heavy rains rather than government policy.

Another general principle of research is called triangulation (triangulate means to form a triangle). The idea is, one particular method or source could be wrong or inaccurate, but if you get several different methods and sources that all agree, it is more likely that your idea is correct.

These are the basics. Also, here is a good website, meant specifically for the methods of environmental history, but useful generally: Learning Historical Research

If you have questions or comments, please comment below!

No comments:

Post a Comment